July 11, 2016

My time at Goulding & Wood lasted about a year, after which I worked a variety of office jobs. During this time I also learned the basics of piano tuning, and began maintaining the baby-grand which my mother played fairly regularly at my parent's house.

My musical life expanded tremendously during those years under the mentorship of Frank W. Boles, then director of music at St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Indianapolis. A combination of uncompromising musicianship and pure charisma, Frank was able to get professional results from a basically volunteer group. He and organist Dwight Thomas, both master improvisors, led worship services in an inspired way that I had never before seen or heard. The organ at St. Paul's was at that time an old rebuilt Möller — a real behemoth with more than a few problems, and Frank hired me to do some spot-tuning on the instrument from time to time (my father agreed to hold keys).

In addition to giving concerts and recording CDs, the choir also toured England every few years during summers. For the duration of one of these trips, Frank appointed me interim organist. Truth be told, the requirements of that job far exceeded my skills at the time, but I leaped at the opportunity. Dwight met with me several times, patiently advising as I stumbled through standard wedding-music repertoire (summer responsibilities would include three weddings, and though I had played many services as a student substitute, I had never played a wedding before).

When seemingly impossible challenges are met with intensely focused hard work, and the timing is right, then rapid growth and development can result. In this case, I improved by leaps and bounds, playing Bach Preludes and Fugues for services, accompanying soloists, and writing or improvising hymn introductions and harmonizations. These formative experiences further strengthened my connection to the King of Instruments and its core repertoire, setting a clear context for the work I would later do when designing my own keyboard instrument.

I remained productive as a composer during this time, but being outside of the comfortable musical bubble of the conservatory, I found it was impossible to organize performances or recordings of my music. I applied to PhD programs in composition and theory at 8 different schools, and was rejected by all of them. At some point I arranged a couple of hymns for choir, and Frank used them in a service. Frank later commissioned me many times to write hymn arrangements and other works for choir, brass, organ, and percussion. Other commissions included a quickly written score (it was done in less than three weeks) for the silent film The Phantom of the Opera by the Baroque Artists of Champaign-Urbana, IL — one of the most intense experiences I've ever had as a composer. (The image of the phantom at the organ is tongue-in-cheek. Personally, I get annoyed by the depiction of organ music as something "scary").

At the end of 1998, I received a phone call from my mentor Peter Hesterman, inviting me to teach theory and composition at my alma mater during his sabbatical. Of course I agreed. I was responsible for teaching ear training, music theory, counterpoint, and private lessons in composition. First-year teachers are rarely very good, but I did relatively well. I felt myself learning much more about the things I thought I knew, understanding the material at a much deeper level than I had before, and I received positive feedback from the students. I especially enjoyed teaching counterpoint, and found I had a great excuse to analyze Bach's music and write some of my own in the same style.

It was during my time as a young teacher that I read Harry Partch's Genesis of a Music (maybe the most famous modern text on Just Intonation, which functions as a sort of gateway into the wide world of tuning for a great many musicians). For me, Partch's book was the second book about tuning I had read, after Martin Vogel's On The Relations of Tone. There was something magical about Partch's text that opened my eyes in a way that Vogel's much more scholarly writing hadn't. I tried some experiments tuning harmonic intervals on my Korg synthesizer by ear according to Partch's instructions, and was convinced that what he was saying was true.

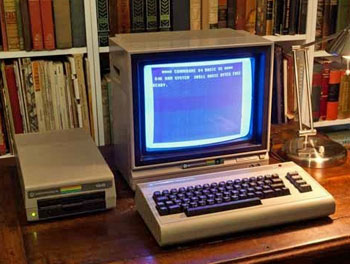

As I performed these tuning experiments, something unexpected happened. There I was, poised motionless at that keyboard in a tiny apartment, when my mind suddenly reached back into memories from my childhood. As I relate this now it seems strange that this epiphany didn't happen earlier during my time as an organ tuner, but I think the reason it happened only at this point was because I was experimenting with a synthesizer. The electronic sounds triggered my memory. I remembered that the programming I had done in my youth (mostly games) on the Commodore 64 included a lot of music and sound effects using that computer's built-in 3-voice synthesizer.

My realization was this: way back then I had actually been making music and sound effects in Just Intonation. I simply had no idea I was doing that at the time. All I knew was that frequency numbers combined in certain ways sounded good or bad to my ear. My memory of this is quite distinct, because I always used the same method in my early programming, which I had arrived at through trial and error. I would take some base frequency value, and multiply it by the numbers 2 through 20, skipping 7, 11, 13, and 14. I sometimes tried other things (also purely by trial and error), but I knew that this method always worked. If you know anything about tuning theory, you'll recognize my method as corresponding basically to 5-Limit Just Intonation, with the addition of 17 and 19 as harmonics that approximate the halfstep and minor third of standard 12-tone tuning. The absence of 7, 11, 13 and 14 is noteworthy. It means that my young totally non-theoretical, untrained ears rejected those pitches, which corroborates basically what music theorists had said for centuries, that basic intervals in just intonation involving the numbers 7, 11, and 13 sound a bit too foreign. Now Partch was challenging my ears to open up to those sounds, and I found that compelling.

It was then that I remembered the moment from nearly a decade earlier — in a practice room, chiding myself for hearing pitches in my imagination that didn't exist on the piano, and I realized that the problem was not with my ears; the problem was with the Western system — specifically the 12-tone keyboard.

I began reading Martin Vogel's On the Relations of Tone in earnest for a second time. While Partch's book had been inspiring and fun to read, Vogel's thorough academic precision was much more appealing and more convincing to me. Putting together all of my experiences up to that point, I finally began to grasp what tuning was all about, and I sensed that I was on the cusp of something important, if not in general, at least for me personally.

This newly found inspiration led to my first compositions for piano in Just Intonation. Since I had adopted 12-tone tuning for so long, it seemed like a good idea to look at standard 12 tone tuning from the new angle I had finally come to fully comprehend. The idea was to interpret the tuning in terms of large ratios, always with a power of 2 in the denominator. The result of this approach is a harmonic system in which, ironically, the intervals normally considered dissonant became consonant, and those normally considered consonant become dissonant. With this work I demonstrated that combinations of pitches on a piano tuned in 12ET, in the right registers, can combine to give perceptually smooth effects normally associated with Just Intonation. This work was a first step for me towards a new way of hearing music, a new way of thinking about what music was and what it could be. It was the birth of many ideas which would later evolve into the H-System.

Near the end of the term, I received an email from the University of Minnesota, where I had applied the year previous, and had been rejected. Now U Minn was inviting me to accept a teaching assistantship in Minneapolis. Having no other plans, and feeling sure that I now had a pretty good idea for a dissertation proposal (involving tuning), I accepted their invitation to begin the assistantship in the fall.

I'll pick up the story there next time.

Best Regards,

Aaron

[ Showing 1 entry | Next entry | Show all entries ]